Jeffrey Ross

The Agony of Aliquorrhea

Intracranial hypotension can occur in a variety of clinical settings and can be grouped by primary or secondary etiologies. We are generally quite familiar with the secondary type of intracranial hypotension, related to prior cranial or spinal surgery, trauma, or prior lumbar puncture, as a cause of postural headache. The primary form (aka spontaneous intracranial hypotension) has now received sufficient attention in the literature that this diagnosis should not be missed or misinterpreted.1,2 Nevertheless, it can present as a therapeutic and, to a lesser extent, diagnostic dilemma.

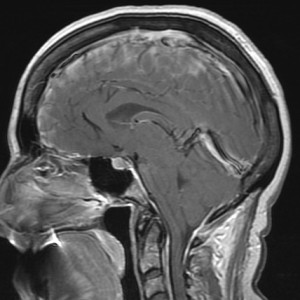

The seemingly varied signs present on cranial and spinal imaging can be explained by the Monro-Kellie doctrine, which states that, with an intact skull, the sum of the volume of brain + CSF + blood is constant.3 Any increase in one of these three factors must be accompanied by a decrease in one or both of the other factors. Regarding intracranial imaging, this is manifested by 1) brain sagging, 2) engorgement of venous structures, and 3) extra-axial fluid collections. Brain sagging (slumping) is shown by flattening of the ventral pons against the clivus, inferiorly displaced third ventricle, low-lying cerebellar tonsils, loss of the basal cisterns, decreased mamillopontine distance, and draping of the chiasm over the pituitary. Venous engorgement is demonstrated by prominent, rounded dural sinuses, pachymeningeal thickening and enhancement, and by pituitary enlargement. Extra-axial collections (subdural effusions and hematomas) may occur when these compensatory mechanisms are inadequate.

Spine changes are slightly more protean. No direct correlation related to brain sagging is seen in the spine. Any sagging that occurs in the spine relates to the loss of turgor of the thecal sac, with a correspondingly enlarged epidural space that often contains fluid and outlines the exiting nerves. Engorgement of the venous structures is present, with thickened and enhancing dura and prominence of the epidural plexus (which in the cervical spine can be quite alarming in appearance). Spinal subdural effusions—or, less commonly, hematomas—may also occur.