Alessandro Cianfoni

In 1987, Deramond and Galimbert introduced the vertebral augmentation (VA) technique, which spread widely as an effective procedure to treat painful vertebral compression fractures (VCFs). In 2009, the New England Journal of Medicine published the INVEST and Australian trials,1,2 the first two randomized blind-sham procedure-controlled trials on VA. The conclusions drawn by these authors were surprising: VA in osteoporotic VCFs was effective but comparable to a sham anesthetic procedure, and therefore mostly related to a placebo effect. Despite microscopic scrutiny and criticism raised by the scientific community on several controversial aspects of these studies, the echo in the lay press was immediate and very loud, and in a short time it seemed that VA was coming to the end of its days. Yet the physicians dealing with the clinical problem of a painful VCF could make little use of the results of the trials, short of offering their patients an unlikely sham procedure.

In the meantime, FREE and VERTOS II, two other trials—on the use of balloon kyphoplasty (BKP) and vertebroplasty, respectively—appeared in the Lancet in 2009 and 2010.3,4 Those trials were randomized and controlled but open label, with the treatment in the control arm being not a sham procedure but the best conservative management. These studies showed benefit for the patients undergoing VA, and offered results and conclusions more applicable to clinical practice, where the physicians could choose between two possible clinical options for their patients. While we are looking forward to the publication of VERTOS IV5—a new placebo-controlled randomized trial on VA—an interesting, recently published article by Luetmer and Kallmes,6 the latter the leading investigator of the INVEST trial, reports that despite clinical referrals for VA at their institution (the Mayo Clinic) having decreased since the publication of their trial, they continue to offer the procedure to a high proportion of referred patients.

Certainly, the intense debate over these studies has promoted a new critical spirit in looking at the VA procedure—at its rationale, indications, and effects, raising ever new questions on this widely used and yet mysterious technique (What is the real mechanism of pain alleviation in VA? Which patients are most likely or unlikely to benefit from it, and why?). Questions keep on being asked and not always clearly answered on the relative indications, similarities, differences, and advantages of the two main VA techniques, vertebroplasty and BKP.

Finally, years of experience with the technique have brought some operators to explore side roads, resulting in some original applications of modifications of the technique. While there has been, in recent years, a wave of interest in the horizons of and publications on the use of VA in neoplastic spine diseases,7-11 the vast majority of these procedures are still performed on osteoporotic VCFs.

It is the scope of this AJNR News Digest to offer a selection of interesting, and in some cases, controversial, articles published in AJNR during the last two years on different aspects of VA applied to the osteoporotic spine.

The first article12 analyzes the natural history and course of pain in patients with painful VCFs treated conservatively. Despite the majority of patients experiencing spontaneous resolution of pain over time, a significant percentage of patients do not recover and remain affected by chronic pain. The authors advocate the delayed use of VA in this group of patients.

The second article13 also deals with patients who have persistence of pain but, in this case, after a technically successful VA. Do these cases represent procedure failures? It is usually quite difficult to ascertain the cause or site of origin of the residual pain in such patients, and here, the authors attempt to locate it with a physical exam under fluoroscopy and through diagnostic block procedures. Their results raise our attention to the facet and sacroiliac joints as common pain generators in these patients.

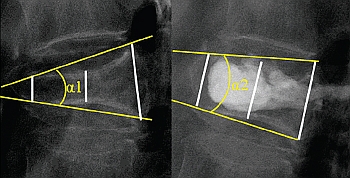

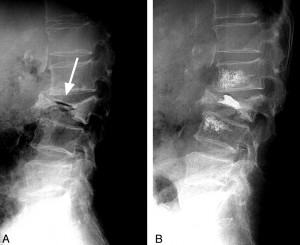

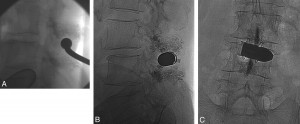

Two more studies, both from the same group, attempt to assess the importance of vertebral mobility, as diagnosed with flexion-extension plain film radiographs, in patients undergoing a VA procedure. In one study14 they conclude that it is the presence of vertebral mobility, more than the VA technique used, whether balloon-assisted or not, that determines the final achievement of vertebral height restoration. It is important to note that though of some possible intuitive advantage, height restoration has not been definitely proven as a clinically relevant aspect of the VA. Their second study15 controversially reports that in patients without vertebral mobility, a technique called vertebral perforation, which consists of insertion and subsequent removal of a needle in the vertebral body without cement injection (a more invasive form of the sham procedures used in the INVEST and Australian trials?), achieves pain reduction, while patients with vertebral mobility need cement injection (a true VA) for pain amelioration. These results force us not to stop thinking about which are the truly right indications for VA, which are not, and which tests to use to select them. In fact, vertebral mobility as diagnosed with dynamic spine plain films might uncover only one aspect of the constellation of elements potentially important for correct patient selection.

And finally, two articles, with confidence, suggest a more deliberate use of the technique, specifically that of cement injection.

Adjacent level fracture after a VCF is a commonly encountered and spontaneous event, but referring clinicians are frequently worried about the possible “domino effect” after VA in patients with severe osteoporosis, also based on some studies reporting such increased risk. Recent data from