Lotfi Hacein-Bey

The technique of fMRI has been around for over 30 years, and DTI for about 15 years. The first application of fMRI was by Ogawa et al, in 1990. In a rat model, this team was able to manipulate the blood oxygen level–dependent (BOLD) signal by inducing changes in deoxyhemoglobin concentrations with insulin-induced hypoglycemia and anesthetic gases. About a year later, Kwong and Belliveau published the first images of cerebral areas that responded to visual stimulation and vision-related tasks.

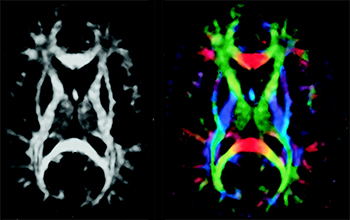

DTI was first described by Basser et al, who were experimenting on a voxel-by-voxel characterization of 3D diffusion profiles, which took into account anisotropic effects (instead of eliminating them, as in standard DWI). Tractography (or fiber tracking) was developed by applying statistical models to DTI data to obtain anatomic fiber bundle information.

Although both fMRI and DTI are now currently available in most scanners, well beyond the framework of academic institutions and research protocols, these techniques are not quite considered “standard of care.” Indeed, the processes that govern the translation of new technology into clinical practice are complex. Even more complex are the processes that lead to establishing clinical practice as standard of care, particularly at a time when established patterns of care delivery are being increasingly challenged and economic difficulties affect all aspects of society, certainly including health care.

However, some challenges, especially with fMRI, go back to basic cerebrovascular physiology. The cerebrovascular response to neuronal activation, also referred to as “functional hyperemia,” was first recognized in 1890 by Roy and Sherrington, who initially proposed a metabolic hypothesis to the phenomenon, ie, mediation via release from neurons of vasoactive agents in the extracellular space. The major role of astrocytes as key intermediaries in the neurovascular response — being interposed between blood vessels and neuronal synapses via their foot processes as modeled in the “tripartite synapse model” of the neurovascular unit — has since been recognized. Although complex, astrocyte response to changes in synaptic activity is primarily mediated by glutamate receptors through changes in intracellular Ca2+ concentration.

In fMRI, contrast is based on the BOLD effect, which reflects local shifts of deoxygenated-to-oxygenated hemoglobin ratios due to local increases in blood flow in excess of oxygen utilization following brain activity. As a result, the foundation of the fMRI BOLD signal is based on local changes in cerebral blood flow that are not linearly related to the metabolic changes inducing the flow change.

Therefore, BOLD fMRI rests on 3 major approximations: 1) the technique does not directly reflect neural activity, ie, generation and propagation of action potentials, synaptic transmission, or neurotransmitter release/uptake; 2) the changes in BOLD signal originate from that portion of the vasculature experiencing the greatest change in oxygen concentration, which occurs in the venules in the immediate vicinity of the active neurons; and 3) more importantly, fMRI signal relies on intact “neurovascular coupling,” the phenomenon that links neural activity to metabolic demand and blood flow changes.

The main reason fMRI is clinically useful most of the time is that under most circumstances neurovascular coupling remains fully intact, unaltered by