Spontaneous intracranial hypotension (SIH), caused by CSF leak along the spine, can be challenging to diagnose and treat. The classic patient with SIH will present with positional headache and the characteristic brain MRI findings of SIH: dural enhancement, venous distension, subdural collection, and brain stem slumping.1 However, patients with SIH often have a variable clinical presentation (eg, nonpostural headache and cranial nerve palsies) and may not have the expected brain MRI findings. Frequently, the CSF leak site is difficult to localize.2,3 Increased understanding of the pathophysiology of SIH has contributed to the advancement of diagnostic imaging techniques, allowing earlier treatment of this debilitating condition. Until now, management pathways have shown marked heterogeneity, which may be in part related to a lack of practical experience, unfamiliarity with recent discoveries, or unsubstantiated conceptions of how this disease process should be diagnosed and treated.4

In this edition of the AJNR News Digest, we spotlight recent articles that have informed the way this condition should be approached for diagnosis and treatment. These articles add to our knowledge of diagnostic techniques for SIH by 1) using brain MRI features5 as well as postmyelographic renal contrast patterns,6 2) discussing digital subtraction and CT fluoroscopy myelographic techniques for SIH work-up,7,8 and 3) proposing a systematic imaging approach for CSF leak localization.2

The aforementioned classic imaging features of SIH, such as thin pachymeningeal enhancement, are not pathognomonic for SIH; pachymeningeal enhancement is commonly seen in postoperative or post-lumbar puncture cases.9,10 Other, more specific imaging features, such as brain stem slumping, are only present in approximately 51% of cases and can be subjective.10–13 In an effort to provide more objective imaging criteria for SIH, Wang et al used the interpeduncular angle as a sensitive and specific measure and reproducible parameter on routine clinical MRI.5

Diagnostic procedures, such as CT myelography (CTM), are routinely performed to identify the site of CSF leak. Kinsman et al described a potentially helpful secondary sign of CSF dural leak and/or CSF venous fistula: the presence of early renal contrast on initial CTM.6 They found that early renal contrast was more common in confirmed/suspected CSF venous fistulas compared with dural leaks.

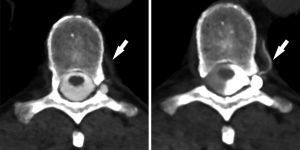

Precise localization of the CSF leak source is vital to guiding directed percutaneous or surgical treatment.7,14 A retrospective review of 5 patients by Kranz et al showed that decubitus positioning during CTM can increase leak detection and diagnostic confidence in some patients with previous supine or prone CTM.7 Fluoroscopic dynamic myelogram followed by decubitus CTM in the right or left decubitus position or bilaterally (based on subtle findings on prior CTM) revealed a CSF venous fistula, with a 507% mean increase in draining vein density (illustrated in Figure 1).7 The authors postulated that increased detection may be due to higher contrast concentration on the dependent side combined with gravity effect.7